Materiality in sustainable investment: in the eye of the beholder

Materiality is a measure of the importance of a piece of information when making an investment decision. But it becomes more complicated when assessing the ESG performance of a company.

Materiality is central to sustainable finance. But what appears to be a straightforward concept is proving slippery in practice—and is triggering disagreements that could have significant implications for how companies disclose environmental and social indicators, and how regulators construct the market infrastructure on which sustainable finance depends.

Put simply, materiality is a measure of the importance of a piece of information when making a decision. But when this concept is used to assess the sustainability performance of a company, it becomes more complicated.

There are literally thousands of raw environmental, social and governance (ESG) indicators that can provide insights into the performance of companies. For any one theme—health and safety, or biodiversity, say—there is a wide variety of potential measures. Across FTSE Russell and Refinitiv, we hunt down data across hundreds of indicators based on the main global sustainability reporting frameworks.

Clearly, some indicators are far more relevant for certain industries than others: the environmental and social impacts of lithium mining will be highly relevant for an electric car company; less so for a clothing group. Geography is also important. Water usage is more important to a company in a drought-prone region than its peers in wetter climes.

But there is also a more profound question for investors to ponder. Should they only track those issues that are directly financial material to a company, or should they also consider impacts on society and the environment that don’t have a clear and immediate bearing on the company’s bottom line?

To take an extreme example, consider a "white label" clothing manufacturer with low brand recognition. Perhaps investors might be less concerned with poor labor or safety conditions in its factories because it does not have consumer brand recognition and therefore faces less reputational risks. The issue of labor conditions may be considered not financially material.

The alternative approach to such narrow financial materiality is known as "double materiality" as described by the EU. This argues that disclosure should not only address the impact of sustainability factors on a company, but also the impacts of the company on society and the environment. This reflects the fact that sustainability information is of interest to a broader range of stakeholders than just shareholders.

This debate is critical to the efforts underway to bring consistency to sustainability standards and reporting, as we discussed in the first blog in this series. Regulators, reporting standard setters, accounting firms, and data and index providers are all working towards common standards to guide sustainability disclosure.

Unsurprisingly, there is as yet no consensus on the materiality question. The EU, in its consultation on reforms to its Non-Financial Reporting Directive, came out in favor of double materiality. It is in agreement with the approach taken by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) which focuses not only on shareholders but also other wider stakeholders. The danger here is that this approach can be perceived as lacking a focus on the concerns of investors.

The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), a US-based organization, takes a narrower, investor-focused view, following the definition of materiality used by the US Securities and Exchange Commission.

However, this approach arguably ignores issues that may rapidly become material over time. Take tax policy: while legally avoiding tax as much as possible while navigating grey areas of tax policy was considered by investors to be normal corporate policy a few years ago, it is has now emerged as a key reputational and financial exposure.

The difference between financial and double materiality is often just about time horizons. What is material for society and the environment ultimately becomes financially material for the company. To return to the example of the white-label clothing manufacturer. In our globally connected world, local whistle blowers, international NGOs and journalists could publicize abuses which, in turn, encourage its retail customers to cut their ties with the company.

Investors have different time horizons too: a day trader will not be concerned about the possible introduction of tighter labor laws in five years’ time; a pension fund with obligations to beneficiaries decades into the future will be far more likely to be scan the horizon for structural changes in the economy and society.

Our view is that materiality is a dynamic concept. As noted above with tax, and indeed most environmental and social issues, it changes over time; few considered that emitting greenhouse gases was a material issue 25 years ago.

It is also highly subjective. An investor does not know which specific sustainability themes for a given company will necessarily become financially material—not even the best analyst can always predict the future. Investment is about competing views of the future, and every investor will therefore consider materiality differently.

Materiality also varies between types of investor. Some hedge funds may favor companies that optimize their tax bills. A universal manager, who owns every listed company across an economy, is more likely to realize that tax avoidance has economy-wide impacts that drag on the performance of its other holdings.

So how do we square the circle between these different views? The standard setters—CDP, Climate Disclosure Standards Board, GRI, Integrated Reporting and SASB—are moving towards an approach to comprehensive corporate sustainability reporting that aims to accommodate these different views of materiality.

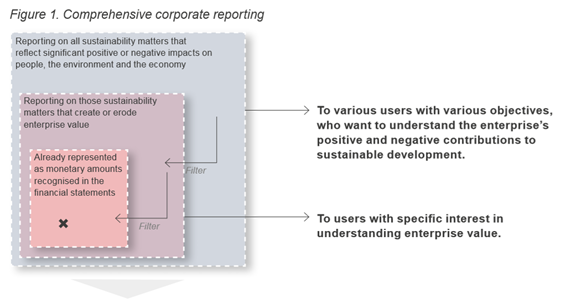

Their Reporting on enterprise value report, published in December 2020 and facilitated by the Impact Management Project, the World Economic Forum and Deloitte, sets out a "nested" approach to disclosure, which places financial reporting within the context of financially material sustainability disclosures and which, in turn, sits within wider reporting of the company’s sustainability matters that impact people, the environment and the economy. Sustainability issues can migrate between these layers as they become more (or less) financially material.

The approach encapsulated by this diagram aims to bridge the divide and nicely captures the concept of dynamic materiality. Financial materiality is found in the pink and purple boxes incorporating an “understanding enterprise value”, while social and environmental materiality is in the blue box. It aims to highlight the “interoperability” of approaches.

We would go further. Rather than distinct categories, we see a materiality on a continuum, based on the time horizon over which it may impact enterprise value, and the level of market consensus around this. As noted above, all impacts on society, the environment or economy can theoretically become material to the company through reputational impact, license to operate, shifting client demand, fines, taxes or regulatory activity.

From this vantage point, there is no contradiction between financial and double materiality. It is a subjective continuum and trying to reach consensus on the materiality or otherwise for every issue for every company is a fool’s errand. Instead, it should be possible to reach consensus on an approach that recognizes the subjective and dynamic nature of materiality, and which gives companies, investors, regulators and other interested parties a framework in which to effectively communicate.

We need to appreciate that materiality, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder.

To learn more about FTSE Russell click here.

© 2021 London Stock Exchange Group plc (the “LSE Group”). All information is provided for information purposes only. Such information and data is provided “as is” without warranty of any kind. No member of the LSE Group make any claim, prediction, warranty or representation whatsoever, expressly or impliedly, either as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness, merchantability of any information or of results to be obtained from the use of FTSE Russell products or the fitness or suitability of the FTSE Russell products for any particular purpose to which they might be put. Any representation of historical data accessible through FTSE Russell products is provided for information purposes only and is not a reliable indicator of future performance. No member of the LSE Group provide investment advice and nothing contained in this document or accessible through FTSE Russell products should be taken as constituting financial or investment advice or a financial promotion. Use and distribution of the LSE Group data requires a licence from an LSE Group company and/or their respective licensors.