US study advocates carbon pricing restructure

In calculating a country’s contribution to carbon dioxide in the Earth’s atmosphere it is important to consider the complete carbon supply chain, according to a new collaborative research project by a group of American scientists.

In calculating a country’s contribution to carbon dioxide in the Earth’s atmosphere it is important to consider the complete carbon supply chain, according to a new collaborative research project by a group of American scientists.

The Supply Chain of CO2 emissions, published as part of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) journals, is the first study of emissions that takes into account the entire carbon supply chain, from the point of its initial extraction all the way to the consumer shelf.

When carbon is extracted from the ground, whether as gas, coal or oil, the fuel is then exported to other countries where they are in turn burned to create the energy needed to make a variety of goods. These products then have the potential to be traded to further countries, before they are eventually consumed. Conventional methods of calculating the cost of the effects of greenhouse gas emissions tend to focus at the point in which the product is consumed. However, the PNAS scientists, led by Carnegie’s Steven Davis, put forward a strong case that the entire process of the carbon life cycle needs to be considered when calculating the cost of their effects.

“Policies seeking to regulate emissions will affect not only the parties burning fuels but also those who extract fuels and consume products. No emissions exist in isolation, and everyone along the supply chain benefits from carbon-based fuels,” commented Davis.

As part of the research conducted by Davis and his team, fossil fuel extraction, combustion and consumption was analyzed throughout 112 countries and across 58 industry sectors. In doing so they discovered that fossil fuel resources remained highly concentrated, with the greater part of exported fuel ending up in developed countries. Furthermore, the scientists found that the majority of countries that imported a lot of fossil fuels also imported a considerable number of products. China was the only notable exception of this trend.

Given the results, the PNAS team concluded that the practical notion would be to impose carbon taxes and relative carbon pricing mechanisms at the extraction level. By doing this it would prevent the relocation of industries looking to avoid carbon emitting costs at the point of combustion. The study highlights the fact that although the manufacturing of goods can move from one location to another, the location of fossil fuel resources remains constant.

“We've moved beyond trying to place blame, because that's just an argument that will never be won,” Davis told Reuters. “The only way it's ever going to get sorted out is if we can come up with anything resembling a consistent, unavoidable price on carbon that applies globally and then the chips will fall as they may.”

The study found that by regulating fossil fuel extraction in China, the US, the Middle East, Russia, Canada, Australia, India, and Norway it would be enough to cover 67 percent of global carbon emissions. As a result of this, those countries that refused to oblige to the legislation would then miss out on the financial benefits of carbon-tariffs spread across the supply chain.

The study found that by regulating fossil fuel extraction in China, the US, the Middle East, Russia, Canada, Australia, India, and Norway it would be enough to cover 67 percent of global carbon emissions. As a result of this, those countries that refused to oblige to the legislation would then miss out on the financial benefits of carbon-tariffs spread across the supply chain.

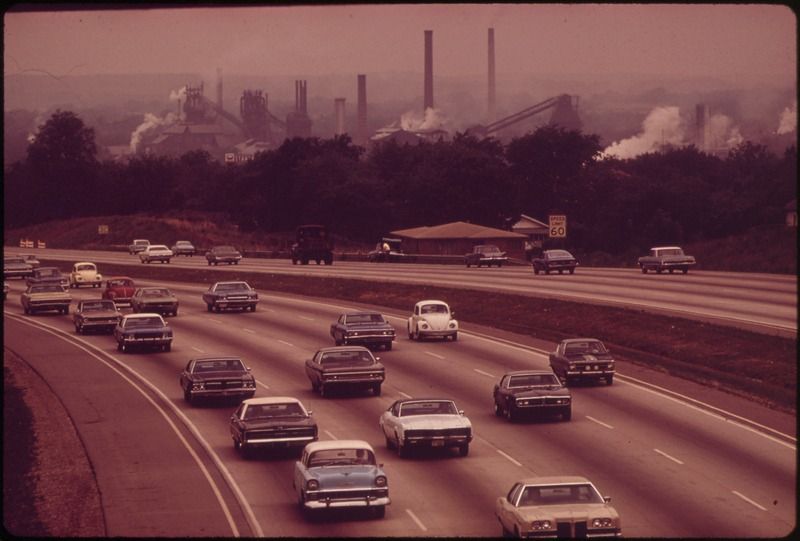

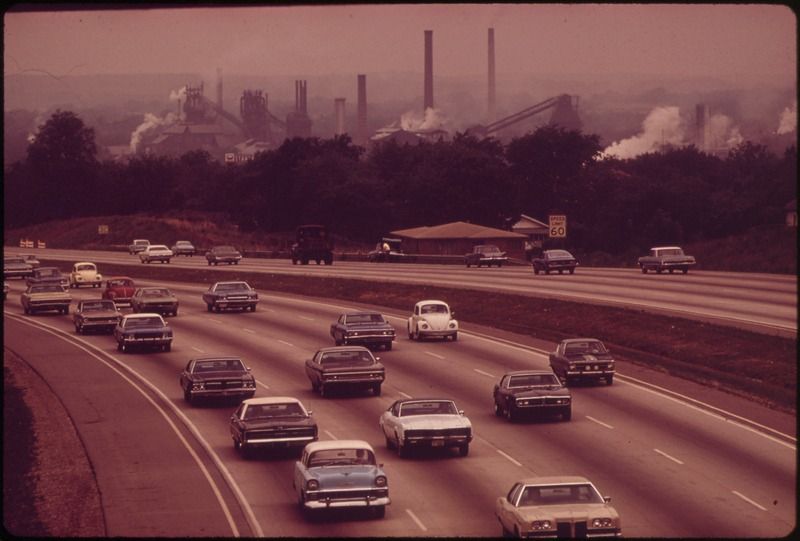

Image 01: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration | Wikimedia Commons

Image 02: Martin Routledge | Geograph.org.uk

Image 03: Nagyman | Flickr